Monday, September 25, 2023, marks the centennial of Sam Rivers’ birth. Rivers was a composer, improvisor, theoretician, scenemaker mentor and instrumentalist of Promethean stature. It’s hard to think of anyone quite like him. So it’s appropriate that his centennial is commemorated by “The Sam Rivers Sessionography,” a new book by Rick Lopez that rivals Rivers in its panoptical audacity.

Originally an online chronicle of Rivers’ performances and recording sessions, “The Sam Rivers Sessionography” is a mammoth, 768-page monster (it weighs more than six pounds), a chronicle of the life and career of Sam Rivers (1923-2011), from his birth in Oklahoma to his homegoing service. It’s easily the definitive source for information about a figure whose vast influence is only now coming into focus, and it’s hard to see anything surpassing it for a very long time, if for no other reason than no sane person would ever attempt such a thing.

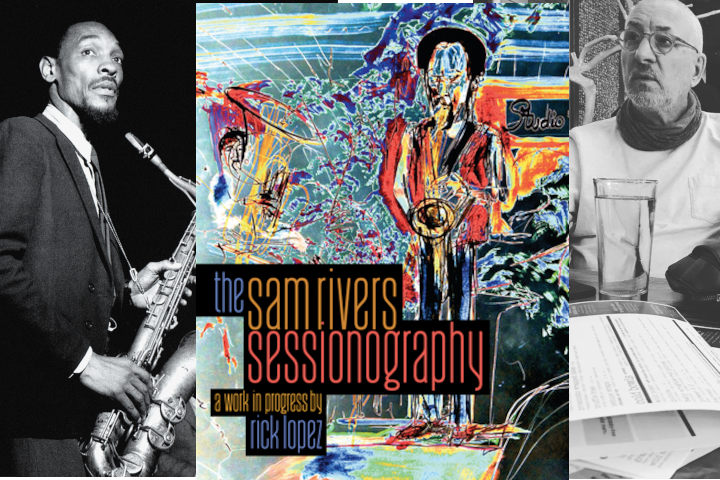

So, what does that make Lopez (who, full disclosure, has been a friend for decades and for whom I proofread the book)? I’ll let him answer that.

“I’m obsessive,” he said on a video call, “about all kinds of stuff. It used to be cigarettes For a while It was cocaine, this and that. Being a vegetarian purist from hell and all kinds of other stuff.”

One of the things Lopez was obsessive about in the late ‘90s was the efflorescence of jazz newsgroups and mailing lists that blossomed in the pre-Web internet era. “One day, I e-mailed Alan Saul at the University of Pittsburgh, who was doing the Dolphy discography, and asked him where the Sam Rivers discography was. And he said, There isn’t one. And I said, Why not? And he said, Because no one’s done it yet.”

Lopez, 70, was not a scholar, nor even a high-school graduate (he has a GED). He is an autodidact and a musician who pursued both interests with the passion and yes, obsession, that seems to be centripetal force that keeps him going. So when Saul told him that anyone could become a discographer, Lopez dove in.

“So that day I wrote to Rivbea Incorporated down in Florida,” he said. “I got buried in emails and lists and information and leads, and Sam Rivers was thrilled that I wanted to do it because, you know, he’s always had that ‘people don’t appreciate me’ thing going on.”

Within a month, on March 10, 1997, the beginnings of the project found its way to Lopez’s website, where it lives to this day in more or less the same no-frills, all-HTML form. It wasn’t long before the scent of Lopez’s project found its way to the hitherto entre-nous community of tape-traders, collectors, musicians, Rivers stans and fellow obsessives who responded with bootleg recordings, clippings, anecdotes and photographs. Lopez followed every lead in a dogged and punctilious search to fix every last detain on the site. One thing led to another and before you know it, yeah, 768 pages.

About those six-plus pounds worth of pages. It took a well-known musical catalyst to turn HTML into a book: William Parker. The great bassist and co-founder of the Vision Festival was another of Lopez’s discographical obsessions. When Parker received the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award in 2013, he asked Lopez to turn his online Parker sessionography into a book. How he did so despite a near-impossible deadline deserves its own essay.

“I determined that I would never do that again,” Lopez, who had run a small press in the ‘80s, admitted. “But after about two years, I thought, you know, it’s Sam. Who deserves a book more than Sam, seriously? I decided like a fool in January of 2018 and wrote to [author] Ed Hazell and said, G*d damn it, Ed. I’m doing the Rivers book.”

He and Hazell made several trips to Orlando, Florida to examine the enormous archive of material that Rivers’ daughter Monique had in her garage. “She told me ‘Yes, you can come down to see the archive because when I moved down here, I was going through all the business stuff with my father. I came across your name and said, “Rick Lopez, who’s that?” And Sam said, “He’s doing the discography. Give him whatever he wants.”’”

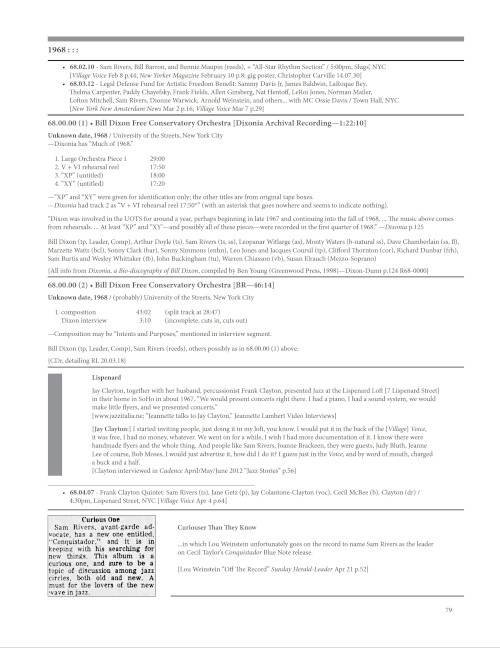

And Lopez, wanted it all—bins of materials that lined two walls of Monique Rivers’ garage. Along with Hazell, who is working on his own book about the loft jazz scene that Sam Rivers served as godfather, Lopez scanned thousands of pages of correspondence, scores, promotional materials and photographs. “I downloaded all the databases, all the gig logs, all the recording session logs,” Lopez said. “I came home, and I think it took me two months just to go through 8,000 images I had, scans and cell phone shots, and get them all dated.”

He taught himself to use design software (the Parker book was, incredibly, laid-out in Microsoft Word) and proceeded to design a book that would meet his exacting aesthetic.

“A session and all of its information cannot run down past the end of a page,” he said. “I don’t like that. I don’t like footnotes at the end of the book. They’re embedded. So every time I added something during the course of three or four years, I would have to adjust maybe 11 pages going forward. To me, it’s an art project. It’s my ass on a plate.”

“[Lopez’] dogged Rivers surveillance (in progress) is a model of independent scholarship, and reading The Sam Rivers Sessionography is a highly immersive experience.”

Kevin Whitehead

And it’s a banquet. In addition to never-before-seen photos and priceless first-hand recollections by colleagues, including many musicians, Lopez also included anecdotes, personal ruminations, eccentric references (“Ren and Stimpy”) and even a dream sequence about listening to Cecil Taylor. “I left that in there,” Lopez said. “It’s going to make somebody smile. Sam had a great sense of humor,”

The manuscript was sent to the printer in April 2022, and after a few more production crises that did not make him smile, the finished book was delivered to Lopez last fall.

The critical community soon got wind of the thing and the response was immediate. Encomia by Kevin Whitehead in Point of Departure, Mike Chamberlain at All About Jazz and Jo Hutton in The Wire (behind a paywall) praised the book. Lopez will join Monique Rivers as a panelist at a centennial celebration in Orlando next month, and an article in the New York Times is expected any day now.

The attention on Rivers’ career is long overdue, and it’s not hard to see Lopez’ book and the festivals devoted to its subject in New York and Los Angeles as the opening events in a revival of interest in this underappreciated musician.

This prospect pleases Lopez as does the attention that he is happy to receive as well as the sales that to date, have nearly covered the cost of self-publishing.

“I get emails from people saying thank you so much. So I know that people are looking at it, dealing with it, using it, even if it’s just to read through it and go, Wow, this guy’s nuts,” he said. “It’s of some use because I get feedback that says so.

But it’s really all just because I can’t help it.”