I get a lot of music for my consideration, more than 460 new releases in 2020. Almost all of them are notable for something, and I’d like to give them their due. So, every week, more or less, I’ll offer hot takes on the releases of the preceding seven days.

If you’ve been wondering how the L.A. studio cats who have been replaced by digital one-man-bands and library music are passing their time, the not-so-short answer might be found in “Out On The Coast” (Basset Hound Music), a three-CD set by The David Angel Jazz Ensemble. Angel, a saxophonist, is one of the 14 players in the little-big rehearsal band and arranged all 22 cuts, also composing 15 of them. What does it sound like? The cover image, a pastel of the California coast at the golden hour, offers a clue. Angel comes from the Gil Evans/Bob Brookmeyer/Bill Holman arranging axis, and the ensemble passages are generally more interesting than the solos. If colorful (though not brightly so), high-calorie arrangements are full of counterpoint are you’re thing, the West coast is the best coast.

If you’ve been wondering how the L.A. studio cats who have been replaced by digital one-man-bands and library music are passing their time, the not-so-short answer might be found in “Out On The Coast” (Basset Hound Music), a three-CD set by The David Angel Jazz Ensemble. Angel, a saxophonist, is one of the 14 players in the little-big rehearsal band and arranged all 22 cuts, also composing 15 of them. What does it sound like? The cover image, a pastel of the California coast at the golden hour, offers a clue. Angel comes from the Gil Evans/Bob Brookmeyer/Bill Holman arranging axis, and the ensemble passages are generally more interesting than the solos. If colorful (though not brightly so), high-calorie arrangements are full of counterpoint are you’re thing, the West coast is the best coast.

The passing of Chick Corea last week is a sad reminder of just how many corners of the jazz world he touched. For his Le Coq Records debut, pianist Bill Cunliffe enlisted bassist John Patitucci and drummer Vinnie Colaiuta, both of whom spent time in Corea’s bands. Cunliffe also chose Corea’s sauntering “The One Step” as one of the nine selections on the 48-minute program, recorded in a single session. Cunliffe seems be recreating the role at Le Coq that Duke Pearson played at Blue Note in the late 1960s: house arranger, de-facto a&r man and valuable sideman, but “Trio” more closely resembles a Prestige Records blowing session. The nine covers range from conventional (“Laura,” “Just In Time”) to the rarely encountered (Monk’s “We See,” and Wayne Shorter’s swooning “Anna Maria”) all played with unpretentious looseness and reliable professionalism.

Corea is also evoked on Cameron Graves‘ “Seven” (Artistry Music/Mack Avenue Music Group). This 33-minute rush of adrenalized thrash metal jazz is what Return to Forever might have been had the late pianist been listening to Metallica instead of Gentle Giant and Yes. Unlike Chick, the Planetary Prince sticks to the piano here, but his meaty-bass heavy riffs, often played in unison with guitarist Colin Cook, hit you with the force of a ransom note. Bassist Max Gerl and drummer Mike Mitchell navigate the additive meters (Graves is fond of seven) at terrifying speeds and the ensemble is tighter than a Republican Congress. But Graves’ music never feels claustrophobic or airless. With its hurtling rhythms and daredevil playing, Seven offers the breathless exhilaration of a high-speed car chase downhill on a steep mountain highway.

Corea is also evoked on Cameron Graves‘ “Seven” (Artistry Music/Mack Avenue Music Group). This 33-minute rush of adrenalized thrash metal jazz is what Return to Forever might have been had the late pianist been listening to Metallica instead of Gentle Giant and Yes. Unlike Chick, the Planetary Prince sticks to the piano here, but his meaty-bass heavy riffs, often played in unison with guitarist Colin Cook, hit you with the force of a ransom note. Bassist Max Gerl and drummer Mike Mitchell navigate the additive meters (Graves is fond of seven) at terrifying speeds and the ensemble is tighter than a Republican Congress. But Graves’ music never feels claustrophobic or airless. With its hurtling rhythms and daredevil playing, Seven offers the breathless exhilaration of a high-speed car chase downhill on a steep mountain highway.

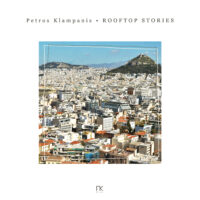

To wait out the pandemic bassist Petros Klampanis retreated from New York to his native Athens where, presumably, he can enjoy the vista of the distant Mt. Lycabettos from his rooftop. That image is on the cover of “Rooftop Stories,” released on his own label. A true pandemic production, the solo recording reveals just how much music one man and a bass can produce. Klampanis conjures and orchestra and sometimes a chorus through effective use of loops. He’s a one-man Ahmad Jamal Trio on “Poinciana,” right down to looping Vernell Fournier’s famous beat and transcribing the pianist’s solo on bass. On “Blue Cave” he takes us into a watery Aegean seascape that might be the Cyclops Polyphemus’ lair. Alone, he offers reading of Steve Swallow’s “Falling Grace” that is the title incarnate.

To wait out the pandemic bassist Petros Klampanis retreated from New York to his native Athens where, presumably, he can enjoy the vista of the distant Mt. Lycabettos from his rooftop. That image is on the cover of “Rooftop Stories,” released on his own label. A true pandemic production, the solo recording reveals just how much music one man and a bass can produce. Klampanis conjures and orchestra and sometimes a chorus through effective use of loops. He’s a one-man Ahmad Jamal Trio on “Poinciana,” right down to looping Vernell Fournier’s famous beat and transcribing the pianist’s solo on bass. On “Blue Cave” he takes us into a watery Aegean seascape that might be the Cyclops Polyphemus’ lair. Alone, he offers reading of Steve Swallow’s “Falling Grace” that is the title incarnate.

Pianist Lex Korten appeared on Tyshawn Sorey’s “Unfiltered,” my 2020 record of the year. So, “A Way Out” (Sounderscore Inc.) arrived with a certain degree of anticipation. Korten is part of a cooperative that includes Israeli guitarist Yoav Eshed, Swedish-Italian bassist Massimo Biolcati and South Korean drummer Jongkuk “JK” Kim. Biolcati is a known quantity from his work with guitarist Lionel Loueke and Hungarian drummer Ferenc Nemeth, but the other two are new acquaintances. Call it confirmation bias, but Korten stands out here. He’s equally persuasive sprinkling winding freebop lines on the title cut as he is with the lush, rubato chording that introduces Kenny Wheeler’s gorgeous ballad “Nicolette.” Eshed contributes strongly characterized compositions and a playful arrangement of “It Might As Well Be Spring” while Biolcati and the quick-witted, quick-handed Kim lay down an active beat. But Korten is the one to watch.

Pianist Lex Korten appeared on Tyshawn Sorey’s “Unfiltered,” my 2020 record of the year. So, “A Way Out” (Sounderscore Inc.) arrived with a certain degree of anticipation. Korten is part of a cooperative that includes Israeli guitarist Yoav Eshed, Swedish-Italian bassist Massimo Biolcati and South Korean drummer Jongkuk “JK” Kim. Biolcati is a known quantity from his work with guitarist Lionel Loueke and Hungarian drummer Ferenc Nemeth, but the other two are new acquaintances. Call it confirmation bias, but Korten stands out here. He’s equally persuasive sprinkling winding freebop lines on the title cut as he is with the lush, rubato chording that introduces Kenny Wheeler’s gorgeous ballad “Nicolette.” Eshed contributes strongly characterized compositions and a playful arrangement of “It Might As Well Be Spring” while Biolcati and the quick-witted, quick-handed Kim lay down an active beat. But Korten is the one to watch.

Al Muirhead was 83 when “Live from Frankie’s & The Yardbird” (Chronograph Records) was recorded in 2018. While it’s not unusual to hear saxophonists and pianists play well in their ninth decade, the list of brass players still active after 80 is a short one. Muirhead is an icon of sorts in Canada and that helps to explain how he gathered an A-list rhythm section that included guitarist Reg Schwager and bassist Neil Swainson for these vividly present sessions. They play silky mainstream jazz with style and taste , providing a lovely frame for Muirhead’s patient trumpet and avuncular bass trumpet, the latter an instrument that should be heard more often. But the real star of the show might be Kelly Jefferson, a tenor saxophonist from the Dexter Gordon school who is fluent, historically minded and effortlessly swinging. Let’s hope we get to hear him into his 80s too.

Al Muirhead was 83 when “Live from Frankie’s & The Yardbird” (Chronograph Records) was recorded in 2018. While it’s not unusual to hear saxophonists and pianists play well in their ninth decade, the list of brass players still active after 80 is a short one. Muirhead is an icon of sorts in Canada and that helps to explain how he gathered an A-list rhythm section that included guitarist Reg Schwager and bassist Neil Swainson for these vividly present sessions. They play silky mainstream jazz with style and taste , providing a lovely frame for Muirhead’s patient trumpet and avuncular bass trumpet, the latter an instrument that should be heard more often. But the real star of the show might be Kelly Jefferson, a tenor saxophonist from the Dexter Gordon school who is fluent, historically minded and effortlessly swinging. Let’s hope we get to hear him into his 80s too.

Have you listened to Mary Lou Williams’ “Zodiac Suite” recently? It’s an astonishingly modern work from 1945, containing the seeds of musical innovations that would take years to flourish in the mainstream. Pianist Chris Pattishall hails from Durham, NC, where Williams taught at Duke University near the end of her life. So, it makes sense for him to use William’s rich material as a launchpad for his debut recording “Zodiac.” Where Williams’ recording was ostensibly for piano trio (the bassist and drummer added little), Pattishall has added a front line of The Westerlies’ Riley Mulherkar on trumpet, and shaggy-toned British tenor saxophonist Ruben Fox to his trio of Marty Jaffe on bass and drummer Jamison Ross. Just as important is producer Rafiq Bhatia, a fellow North Carolinian whose subtle but important post-production techniques lend the recording an appropriately unearthly atmosphere. It’s a fascinating reimagination of Williams’ 12-part suite, boldly conceived and convincingly played. With this auspicious beginning, the stars seem aligned for Pattishall to have a significant career.

Have you listened to Mary Lou Williams’ “Zodiac Suite” recently? It’s an astonishingly modern work from 1945, containing the seeds of musical innovations that would take years to flourish in the mainstream. Pianist Chris Pattishall hails from Durham, NC, where Williams taught at Duke University near the end of her life. So, it makes sense for him to use William’s rich material as a launchpad for his debut recording “Zodiac.” Where Williams’ recording was ostensibly for piano trio (the bassist and drummer added little), Pattishall has added a front line of The Westerlies’ Riley Mulherkar on trumpet, and shaggy-toned British tenor saxophonist Ruben Fox to his trio of Marty Jaffe on bass and drummer Jamison Ross. Just as important is producer Rafiq Bhatia, a fellow North Carolinian whose subtle but important post-production techniques lend the recording an appropriately unearthly atmosphere. It’s a fascinating reimagination of Williams’ 12-part suite, boldly conceived and convincingly played. With this auspicious beginning, the stars seem aligned for Pattishall to have a significant career.

Michael Wimberly, who succeeded the recently departed Milford Graves at Bennington College, has sterling avant-garde credentials earned while drumming with Charles Gayle and William Parker. But on you won’t find those luminaries on “Afrofuturism” (Temple Mountain Records). Instead you’ll hear vocalists Joss Stone and Gary Pinto, kora player Foday Musa Suso and Wimberly himself, not on drums, but playing mostly hand percussion, vibes and keyboards. Wimberly had a hand in the composition of 11 of the 13 songs that embrace r&b and Afrobeat, taught Prince-ly funk and Soulquarian languor. Special credit—especially on a drummer’s record, goes to Julian Joseph whose drumming is loose but intensely grooving whether he’s playing whipcrack funk or floating Malian beats. Afrofuturism? I’d call it Afroaffirmation. This is joyous music for the here and now.

Michael Wimberly, who succeeded the recently departed Milford Graves at Bennington College, has sterling avant-garde credentials earned while drumming with Charles Gayle and William Parker. But on you won’t find those luminaries on “Afrofuturism” (Temple Mountain Records). Instead you’ll hear vocalists Joss Stone and Gary Pinto, kora player Foday Musa Suso and Wimberly himself, not on drums, but playing mostly hand percussion, vibes and keyboards. Wimberly had a hand in the composition of 11 of the 13 songs that embrace r&b and Afrobeat, taught Prince-ly funk and Soulquarian languor. Special credit—especially on a drummer’s record, goes to Julian Joseph whose drumming is loose but intensely grooving whether he’s playing whipcrack funk or floating Malian beats. Afrofuturism? I’d call it Afroaffirmation. This is joyous music for the here and now.